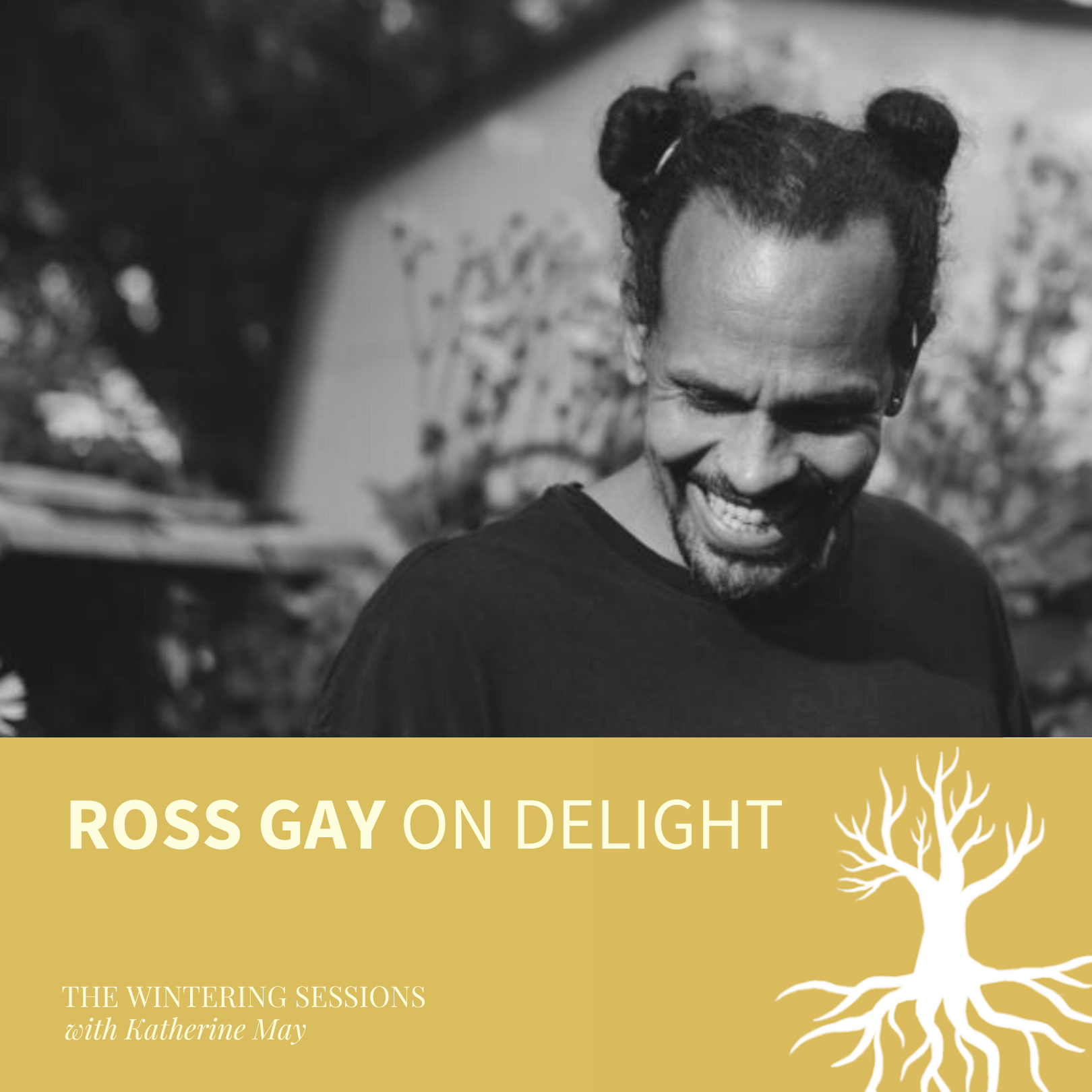

Ross Gay on delight

The Wintering Sessions with Katherine May:

Ross Gay on delight

———

This week, Katherine talks to Ross Gay about finding delight in dark times.

Please consider supporting the podcast by subscribing to my Patreon where you’ll get episodes a day early (and always ad free) along with bonus episodes and more!

Listen to the Episode

-

Katherine May:

Well, hello. I'm Katherine May. Welcome to the Wintering Sessions. I think this is my most dramatic entrance yet. I'm standing outside in my back garden and it's raining a little, but it's also thundering and lightning. And I'm one of those people who loves thunder and lightning. I love the drama. I love the way it kind of takes over. When it's thundering, you can't do anything else. You have to engage with the thunder. I also love the sound around it. I love the sound of rain in trees and all the leaves rustling and the way that you can almost hear the garden drinking it up at this time of year. I don't know why people don't like rain more, honestly. It's one of my favorite things. In fact, and I'm going to attempt a really lame segue here. You might call it a delight.

Katherine May:

This week, I've interviewed Ross Gay, who talks so beautifully about delight. What he expresses so perfectly is this really quite delicate emotion of just being pleased by something. And it doesn't have to be a demonstrative thing. It's normally a point of contact for him, a way that he's making a connection with the people around him. Sorry, I have to stop here because another delight has landed in my garden, a little robin who seems to be really friendly this year and who comes to see me every day at the moment. I was in the kitchen yesterday and I was doing the washing up and I suddenly looked through the window and there was his little face pressed right against the glass. And I screamed. I feel a bit bad about that now. Sorry.

Katherine May:

Anyway, Ross Gay, just as delightful as the robin. I think reading his book, The Book of Delights makes you really think about the delights in your own life and to engage with it is to start to notice the things that delight you, that just raise a smile. Anyway, I will leave you to hear the conversation, but I enjoyed talking to him so much and not least, as I do mention a few times, because he's the first man on my podcast. I'll see you all in a bit.

Katherine May:

So Ross, welcome to the Wintering Sessions. Thank you so much for joining me. I've just told you this story, but I'm going to tell it again out loud because, as listeners may notice, you are my first ever male guest, which is quite the moment, I think, probably not for you, but for me. And it was never my intention not to ever talk to men, but I just got to the point where I realized I'd only spoken to women and then it became like a thing that I couldn't get through, which is probably the wrong way to approach it. But then I began to think, right, I have to have the absolutely perfect male first guest. And then after that it will be easy. And according to my listeners, you are it. So that's kind of a nice thing to be, isn't it?

Ross Gay:

I'm proud to be, yeah. Yeah. Well, thank you for that.

Katherine May:

Yeah. I mean, I think that's an accolade. That's like getting an Oscar or something on a very small scale.

Ross Gay:

Yeah. Yeah.

Katherine May:

But I was thinking about, what was it that made people feel like the perfect person to come into this space? And I think it's not just because you talk about delight in and of itself. I think it's because you talk about delight as a facet of a kind of complicated and often difficult and often dreadful life. And that's the fit I think.

Ross Gay:

Yeah. Yeah.

Katherine May:

Let's dig into some of that anyway. Delight is, I don't know. I listened to your book on audiobook and I've just reread it this morning actually, to refresh my memory. And I found again, I couldn't put it down. When I was listening to the audiobook, I kept driving round in circles so I could keep listening for longer because actually, it's not often, we think about those beautiful moments in life in really simple terms. Can you unpack what you mean by delights? What are the delights you think about?

Ross Gay:

Yeah, it's such a good question. So it's fun, because I'm writing book two. I'm calling it Book Two of Delights. So it's been five years since I wrote... The first book I wrote August 1st, 2016 to August 1st, 2017. So August 1st of last year I started a new one. So I'm kind of rethinking it. And I realize people often ask me what I mean by delight, kind of to define it. And I realize I'm like, why don't I have a great definition? But the more I write, the more I think about it, the more I am kind of inclined to think that it has something to do with surprise or realizing something that you didn't realize before. You may have been aware of it, but you maybe haven't been aware of it necessarily. I mean, it's just like...

Ross Gay:

I was walking the other day and I saw these kids playing tag and I felt so glad to see kids playing tag. And I thought, oh, maybe because I'm in this kind of, whatever you call it, delight practice of sort of articulating the thing that makes me feel that thing, that we're calling delight. But I noticed it, I recognized and I thought, oh, tag, what a great game. I love that game. And I love the fact that seeing these children playing this game without any adults around, it's just like... And then from there, it's like the kind of revere of those simple games that we just know how to do. But there is definitely something about surprise, about something being made sort of available to us that prior to the sort of occasioning event, whatever, the hummingbird, boom, then you're like, whoa, hummingbird.

Katherine May:

It delights me that you live in a place with hummingbirds. I've never seen a hummingbird. I was very excited by your hummingbirds.

Ross Gay:

They're delightful. They're amazing.

Katherine May:

And praying mantises too.

Ross Gay:

Yes. Yes, that's right. That's right.

Katherine May:

We have such boring insects compared to you. I don't know. I just, I'm really disappointed in my insect life now.

Ross Gay:

Yeah. But actually, and that's actually a great point too. I was visiting this school here and I read a couple of these delights and this kid said to me, "You seem like you have a really eventful life." And I said, "Nah." I said, "I think I paid very close attention. I describe my life. I pay attention to my life," which is my way of saying, even those boring insects over there, I bet if you got close enough, it'd be like, whoa.

Katherine May:

Yeah.

Ross Gay:

So I also think that that just makes me think that it's both, that sort of surprise, but it's the kind of surprise that's available almost anytime you look close enough.

Katherine May:

So it's unexpected, but I think there is like a childlike thread in your delights. Not necessarily as closely connected as playing tag, but there's something about fresh eyes and seeing things anew.

Ross Gay:

Yep. Yeah, exactly. Yeah. Surprise. Surprise. Yeah, seeing something new. Yeah, I think that's probably also part of... Well, what's moving to me about thinking about these things or reading them when I write them or writing them is that I realize how often I am sort of walking through the world with a kind of, what would you call it? Like just not really paying attention. The way like, part of what are the qualities, I think, one of the sad qualities of growing up is that we cease paying attention. We kind of got it down, which is why kids take so long to walk down the street. It's because possibly, they're like, what in the world is that thing?

Katherine May:

I think about this every morning where my son is brushing his teeth and I have to stand over him, because otherwise it literally takes an hour. And he's like, "Oh wow. Look at this little blob of toothpaste on the sink. That looks like a Pikachu. And, "Oh, look over there." And it could just go on for ages, like these tiny grains of fascination, which are, I mean, honestly, I shouldn't be frustrated with them because they are so beautiful. We need to recapture those a little bit as adults, I think.

Ross Gay:

Yeah. Yeah, totally. Totally.

Katherine May:

I think probably there's something in there about being a poet as well, that trains you into this kind of granularity of experience. Is that something that you feel about your practice?

Ross Gay:

That's a great question. I think one of the things that I try to do in my poems, like I am very, yeah, that granularity, that's a good word for it. I am interested in very small details, whether it's details of sound or details of syntax, which to a poem is everything. But it can be very sort of, like the arrangement of two words can mean everything of course, but it's also, I'm very interested in poems. I'm interested in images, sort of precise ways of depicting images.

Katherine May:

Right.

Ross Gay:

And I think in order to do that, often I spend a lot of time sort of really looking hard at what this thing, what the actual stand of garlic greens in the wind actually looks like, what does that look like? Is it this, is it that? Yeah, it's a good question. I feel like I've been doing that for a while, so I feel like it maybe lends itself to just taking time and really trying to really look at something.

Katherine May:

Yeah. I mean, I didn't always write, I started writing in my mid, late 20s. I always wrote as a child, but I came back to it and I realized that I had always meant to carry on writing, but didn't. And I felt like I had to relearn that level of observation and that it made me conscious that I'd almost hit a point that I thought I had to stop noticing those small things, because it was part of the kind of putting away childhood, almost. That to be an adult, you had to be almost deliberately more cynical and jaded and weary with the world and find it all really boring. I mean, that's the terrible thing that being a teenager does to you, I think. It's like this act of violence against noticing.

Ross Gay:

Totally.

Katherine May:

And I think I've really consciously relearnt my noticing actually, but now it is just elemental to me and I can't stop. But yeah, it's interesting to think about how absent it can be.

Ross Gay:

Yeah. I think you're exactly right. I do think it's... Yeah, you can see it as a kind of training into adulthood, is that you put wonder aside and you put enthusiasm, except about very sort of mandated things aside, but for the most part you... The kids who, when they're 17 are just like, ah, look at this [inaudible 00:12:08]. Oh my god. Those kids might be hanging out, but it's a small group. But that's really the kid that I'm trying to be. I'm trying to be like that about the bird songs, about what my friend is wearing, about the music that I love, about the food that someone has made me. Yeah, I'm trying to be that.

Katherine May:

Yeah. It's a good way to be. And I think also a lot of your delights are about human connections made, like fleeting ones, just little gestures of... Again, it's of seeing people in lots of ways, but you often talk about touch, I think.

Ross Gay:

Yeah, that's right. That's right. Yeah. Yeah, I did. At some point, I noticed that so often the lights were these examples of very sort of small interactions between people that you otherwise, you just might not notice, but there were small, little interactions between people. Like there's one on the... There's kids running down the aisle in a plane and people can't help but poke this kid in the tummy. And it's just like, it's remarkable. There's all these sort of gestures and, like you say, touchings and stuff that happen in the book. I noticed at some point that those, I was sort of witnessing these moments of care and then those moments of care made me inclined to be like, hey, did you notice that moment of care?

Katherine May:

I mean, assuming your book was written before the pandemic, which it must have been if it was five years ago, I guess maybe that's one of the things we missed, but maybe we couldn't articulate it, was those casual instances of connection that like, I think that was part of what made life feel so flat, was not connecting with strangers on a minute level. I certainly began to really miss that, just smiling at people while I picked up my coffee or something.

Ross Gay:

Absolutely. Absolutely. It's fundamental. It's fundamental. Yeah.

Katherine May:

But I don't know if we realize it's fundamental, actually. It seems so trivial. Even as I'm saying it, it seems so trivial. I always talk about myself as having reclusive tendencies. And I think I'm probably lying when I say that, because when I really was shut away from other people, I missed people so much. I missed their randomness, their ability to bring randomness into my life and unexpected things and to throw my day off course and break my plans almost.

Ross Gay:

Yes. Yes. That's exactly it. That's exactly it. Yeah, me too. It's funny. You wouldn't guess this from the book, but I'm also sort of reclusive. I can be social and then I kind of retreat, but being in company is as important as anything in my life. The exchange of the small, loving, almost invisible exchanges between my friends, who I just said it came out of my mouth, my friends at the coffee shop, just that simple daily interaction is, to me, among the fabrics of life.

Katherine May:

Yeah. Actually, I got to interview Cole Arthur Riley a couple of weeks ago, and she made this brilliant point, which was that we are so often told that to have a intellectual or spiritual life, we should retreat from other people and that that happens alone and it only happens in solitude, but that actually, particularly her sort of black upbringing meant that community was vital to her spiritual encounter with the world. And I kind of thought, yeah. Do you know what? I've believed that for a long time as well, that to be clever enough, I have to be isolated almost. And it's not true, is it?

Ross Gay:

Yeah. Yeah. That's right. That's right.

Katherine May:

So interesting. I'd like to talk to you about your garden.

Ross Gay:

Oh please.

Katherine May:

Yeah, I know from reading you that you'll want to talk about it. But I have to confess upfront that I am the world's most hopeless gardener. A friend came around to my house for a drink recently and he was sitting in my garden and he said, "I don't know what you do to gardens." At the moment, the whole right-hand side of my garden is just mud. And I planted it out. Like somebody came and helped me to take down all the trees that had overgrown. I'd planted weird plants as usual. And he helped me to take them all down because they were all crowding each other out. And it was mainly bindweed. And in October, we planted out all new plants and I was like, "Is this the right time of year?" He was like, "Absolutely. This is just perfect. They will just bed down over winter. They're the right plants." Not a single one has survived over winter and I'm back with bare mud again. I cannot, I just, I don't know. I am the curse on gardens. You however, are not, right? Tell me about your garden.

Ross Gay:

Well, yeah, it's really great. It's funny, I told you I'm writing these delights. And one of the things that... A few years ago, I planted a bunch of sunflowers, big old sunflower. I had some sunflowers seeds lying around. And those sunflowers, some of them were these mammoth, I think they call them and they're 10 feet tall.

Katherine May:

Oh, wow.

Ross Gay:

Oh, they're beautiful. And at the end of the season, these gold finches, other birds too, but gold finches get on them and they just eat them and they send the seeds everywhere. It's amazing. So one of the beautiful entanglements of the garden is that those flowers grow up and then the gold finches plant them all over the place. So now, this time of year, my job is to transplant them, dig them up and plant them where I want them

Katherine May:

Kind of marshaling some flowers.

Ross Gay:

Yes, yes. And it's so neat. It's like this total collaboration. They do the hard work for me, the birds, but I was just replanting them where I wanted them to be. When you transplant plants often, you may or may not know this, but when you transplant them, they look kind of weary.

Katherine May:

You know I don't know this.

Ross Gay:

You will know this. You will know this.

Katherine May:

Carry on.

Ross Gay:

They look kind of weary. So I have that feeling that maybe you have, like often when I'm gardening, which is like, oh no, I think maybe I just killed these transplants, I just killed these sunflowers. And then I water them a little bit. And then four hours later, they're standing up and they're happy and they're ready to go. So anyway, that's actually one of the feelings that I noticed this year as I was gardening that although... I've been gardening for 15 years, so I'm basically a baby gardener. I'm 47. I started when I was like [inaudible 00:19:18]. But almost every time I plant stuff, I still, when it comes up, I'm like, what in the world? How this possible? Even though I know that's just what it does, that's the beginning. We can go on and on.

Katherine May:

No, I mean, please do. And I keep asking gardeners about gardening, because I feel like one day something's going to go into my head that explains to me why I kill everything so thoroughly. I think [inaudible 00:19:47]. Please tell me.

Ross Gay:

Yeah. Yeah. I wonder what... It sounds like you have bindweed.

Katherine May:

Oh, so much bindweed. Yeah. And couch grass as well. All of that. Yeah.

Ross Gay:

Okay. Yeah. I'm finding trying to figure out more and more what just grows well without a lot of intervention or tending and it sounds like [inaudible 00:20:11].

Katherine May:

It's bindweed.

Ross Gay:

That is a bindweed. So that's one thing, which is also a kind of patient relationship to the garden.

Katherine May:

Yeah. That does make sense. I think two things. I think, one, my dog digs everything up, which is not my fault. I killed things before I had a dog, but now the dog is not contributing frankly. But I think my bigger problem is I kind of like the weeds. They come up and I kind of think, oh, it's a shame to take that away. It looks so happy there. Over-empathizing with the weeds, I think is one of my gardening woes. And then obviously they take over and kill all the stuff I planted. There's a little bit of me that still thinks, oh, well, maybe they're meant to be there. It's bad. I need deprogramming.

Ross Gay:

Sounds reasonable to me. Sounds reasonable.

Katherine May:

Well, yeah. But I mean, I find plants really fascinating. And I just want to watch them grow and see what they do. I'm always really enchanted with plants, my friend has taught me to call them volunteers, that just appear in your garden and want to be there and grow. I just think they've got a right that I can't disrupt.

Ross Gay:

Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. They also have a knowing, that's the other thing. It's like sort of to interact with that knowledge in a kind of like, I was going to say non in positional way, but like in a way that's sort of more collaborative. So actually really wondering with the garden, what wants to grow here as opposed to I want this to grow here. That can be a struggle. A lot of the language of gardening is the language of war. And it's just like, what if we put that aside? What if we put that aside and they're kind of like, huh, I wonder. Clearly you thrive here. What else might thrive here?

Katherine May:

Yeah. There's a great kind of, I mean, I think it's true in America too, but this great British obsession with the lawn, like having this great big expanse of short grass.

Ross Gay:

Yeah. Totally.

Katherine May:

And I can't engage with that. I don't find it interesting and I don't know what to do on grass and I'm a seaside person and I don't want to cut it. And actually, I mean, let's add another aspect to why my garden doesn't grow. I'm really lazy. I hate the work. I think we're learning a lot here. Do you spend a lot of time though? I mean, does it take a lot of your time? And I presume that's positive for you.

Ross Gay:

Well, I like being in the garden, but I'm also like, the more I learn how to garden, the more I'm sort of realizing how much I actually want to be working in the garden. I often think this, like if I was to make my living as a farmer, what would I grow? And I think I would grow things like garlic and sweet potatoes and potatoes and things that have one big harvest time that you manage for a little bit, and then they take care of themselves. The more I learn how I am, I realize that is part of my pace too. I don't actually like to have to do stuff every single day.

Katherine May:

Yeah. That really bothers me too.

Ross Gay:

Yeah. Yeah. There are plenty of things to grow and I love growing those things that to some extent it's like you put them in, you make sure they take okay, and then you're kind of, all right, we're going to check in with you periodically and make sure you're watered, but you're going to take care of yourself.

Katherine May:

Yeah. Okay. I feel like, maybe I might do better this year, but I've left it too late already, I presume. Yeah, big sigh.

Katherine May:

I'm just interrupting you for a moment to ask if you would consider subscribing to my Patreon. Friends of the Wintering Sessions, get an extended edition of the podcast a day early, the chance to put questions to my guests, a monthly bonus episode, and exclusive discounts on my courses and events. Most of all, you help to keep the podcast running. To find out more, go to patreon.com/katherinemay. Do take a look. Now back to the show.

Katherine May:

I want to ask about the context in which you're writing about delight and about loveliness and happiness and all those very simple pleasures, because yours, isn't a book that's like, you must be blindly optimistic. You must be grateful for everything. You must just see the good side. Everything's fine. Everything's going to turn out. There's a real undercurrent of dark things happening behind it, isn't there?

Ross Gay:

Oh yeah. Yeah. Yeah. It's interesting when I hear even the word optimistic or hope with this book, I think, I understand that response, because I think it probably feels for other people, it offers, I'm just realizing this now. It might offer other people, maybe readers, a sense of optimism or hope. But I don't think this book, the way I think of those terms, that this book, isn't really actually interested in that. This book is actually interested in attending to the day-to-day care we're in the midst of, or variations of that. The premise of the book is like, yeah, it's fucked. Shit's fucked up.

Katherine May:

Yeah, that's right. Yeah.

Ross Gay:

Yeah, of course, no doubt. And there will periodically be... Actually, in this new book two of The Book of Delights, I find myself wanting to respond to that a little bit because periodically people will sort of be under the impression that... How to say this? To some extent, I think maybe it is like, they so badly want the book just to be a happy book.

Katherine May:

Right.

Ross Gay:

And I'm like, read the essays.

Katherine May:

Yeah. You wouldn't have to read very far. Yeah.

Ross Gay:

You don't have to read very far. And you know, it's talking about, there is the horror and there is the bloom. And they do not exist separate from one another, at least in my grownup life. And it's kind of interesting, as I said, I was sort of thinking the grownupness, it feels like a grownup thing. Like I have this essay on joy in the book. And actually, this new book I have coming out October, it's a kind of expansion in a way of that consideration that happens in that essay. It's a childish endeavor to imagine that we can just be happy. Put it like that.

Katherine May:

Yeah. Yeah.

Ross Gay:

Grown people know it's not all just happy. That's just like being grown. And it's funny because I feel like part of that, I'm making a connection here that I don't quite know how to make, but because we started talking a little bit about how the tamping down of enthusiasm and maybe even delight that comes with growing up, on this one side, it's a kind of, you tamp down a relationship to a full life to become a grownup. But it's also a quality of being a grownup to have a full life, to be like, yeah, I know it's terrible. And it's wonderful. As far as I'm concerned, that's how it is. In a way it's sort of the enthusiasm or the close looking or the paying attention, it's being able to attend to the sorrow. And it's also being able to attend what flummoxes us with delight. They are not mutually exclusive. And it feels to me like, childish to imagine that they are. And also, it makes sense for a kind of dumb consumer culture, because then you can buy a thing that will make you happy.

Katherine May:

Yeah. I think there's something about full humanity in... Actually, I think it's something we've both got in common in our work, that we're thinking about bringing your full humanity to the fore, like the light and the shade and how that is completely interconnected and not in any way separable. And that it's not even desirable to separate it, because the pleasure of the joyful bits reside in that background of knowing exactly what life's like. And I increasingly realize that this obsession with happiness as a separate strata that we're supposed to isolate off and seek is such a Western 20th Century invention. Even my grandparents would not have recognized this concept, that it was attainable in a pure sense and wouldn't have found it an interesting idea almost. We've got here very recently. And I think we're realizing pretty quickly that it's not an attainable goal.

Ross Gay:

Yeah. You said the word gratitude too. And I think, to me, the word gratitude implies the full grownup understanding of the profound heartbreak, that it's just part of being a creature. And gratitude is sort of, and yet there are trees literally making it possible for me to breathe. There are literally creatures that a kind of conventional way of knowing would say are discretely inside of my body at this moment, making it possible for me to live. If they go away, I will die. And a practice of gratitude, I think, is serious. It is grave. It is understanding. It is understanding. Hard to be grateful when you don't have some kind of relationship to the sorrow.

Katherine May:

Because feeling gratitude is a huge part of what I do every single day, what I really resent is the constant entreaty to tell other people to feel grateful. I feel like that's something you have to come to by yourself. And that actually, it's not an instruction. It's got to be authentically felt. It's got to be traveled to almost.

Ross Gay:

Yeah, yeah. Yeah. So often that kind of grateful, the compulsion to gratitude or being compelled to gratitude, so often it's being told by people who could evict you.

Katherine May:

Yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah. It's a power relationship.

Ross Gay:

It's a power relationship. Yeah. And that's a completely different thing and it's a weaponized thing. So what I'm talking about, I'm not talking about that.

Katherine May:

No. No, no.

Ross Gay:

I'm talking about this actual thing that understands that we're profoundly entangled, we're profoundly entangled and it's by the generosity of the earth. That's who I'm always sort of... The earth of which we are all a sort of expression of.

Katherine May:

Which grow things for you and not for me. Yeah.

Ross Gay:

But you probably ate today too. So [inaudible 00:31:50] to all of us.

Katherine May:

Yes, I did.

Ross Gay:

That's what I'm talking about when I say gratitude. It's funny, I have this essay in this new book, and it's talking about gratitude. It's talking precisely about the thing you just said about what I would call a kind of brutal compulsion to effectively, to feel grateful that we have not killed you. To feel grateful that we didn't put a highway through your neighborhood. You should feel grateful we still let you live, even though there's lead in the water, et cetera, et cetera. This essay in the book is sort of acknowledging that and being like, we're not talking about that. We're talking about this other thing.

Katherine May:

My next book, which is coming out next year, it started off as a book about humility. And I was really interested in the concept of developing a sense of humility and how nourishing it is to feel humble. But I had to stop writing it because the more I dug into it, the more angry my own subject matter made me, because it was just abundantly clear that humility had so often been weaponized against other groups. It was something that we, particularly as white Westerners, I guess, kind of praised other people for having in what was actually the most condescending way possible. Like we admired the humility of Gandhi because ultimately we felt like he didn't cause too much trouble. He didn't harm us, so we were willing to admire that. Whereas we are critical of people who stepped up and said, no, actually I'm really furious with you and I'm going to do something really direct about it.

Katherine May:

And I got totally tangled up in it and I had to stop writing about it because I ultimately felt like, actually it wasn't my story to tell, that actually there's a whole hidden history here of the way we've demanded positive sentiment from other groups without ever applying it back to ourselves. And we've seen it as admirable from a distance without really feeling an obligation to equally take it on. And I feel like the gratitude conversation we've got to recently in the mainstream has often touched in that place as well for me.

Ross Gay:

Yeah, totally. Totally. It's funny, the word humility. It's interesting that word, the etymology of it, I'm pretty sure is the humus.

Katherine May:

Of the soil. Yeah.

Ross Gay:

Of the soil.

Katherine May:

Yeah. Yeah.

Ross Gay:

And it's funny in that in your first sentence, you said humility and you said dug. Both of them are soil metaphors. And I think there's something, like a true humility, I think. I'm just sort of wondering, in relationship to the question of gratitude, like humility to recognize that we are of the soil or something.

Katherine May:

Yeah, exactly.

Ross Gay:

That's a recognition of, again, the word entanglement or recognition of-

Katherine May:

Yeah. Rootedness.

Ross Gay:

Rootedness, beautiful. And the compulsion to being compelled to be humble is not that. It's not that. It's effectively saying, you're from the soil.

Katherine May:

And I'm not.

Ross Gay:

Yeah, it's that kind of thing. Yes, it's that kind of thing.

Katherine May:

Yeah. And I think there's also something about the practice of humility. Oh god, like I'm having this conversation now instead of writing a book about it. Forgive me.

Ross Gay:

No, no. Not at all. Say it.

Katherine May:

But it's about recognizing that you are exactly the same as everybody else. And part of that is not being any worse too. Like not punishing yourself harder for transgressions that you'd forgive of other people or that you'd actually find endearing in other people. Like, oh, I spilled my glass of milk and I'm going to berate myself for the next five hours about it. Whereas if your friend spilled their glass of milk, you'll be like, oh, don't worry, I'll get a cloth. That's fine. And so humility, it works in the opposite direction as well. There's a sense that sometimes we're being too humble, like forcefully humble and we're punishing ourselves and taking ourselves lower than where the equilibrium is supposed to be. It's a really complex idea when you start to look at it closely.

Ross Gay:

Yeah. I love that. I love that so much, that kind of like possibility for.... I mean, when you say that like of... I was just having that feeling the other day that I was getting on myself about something that, exactly how you said, if someone else had done it, I would've been like, how sweet. That kind of self, being tender-

Katherine May:

To yourself.

Ross Gay:

To yourself. Yeah. Yeah. It's funny. That ends up being one of these things that shows up in The Book of Delights a bit. And I think it's partly like... I don't know what it is. If it's like getting a little older or something and just sort of being like, golly, you have spent so much time really, really berating yourself and judging yourself and being unforgiving.

Katherine May:

And what a waste that is.

Ross Gay:

What a waste, what a waste. Yeah. Yeah. I mean, that's actually, to kind of talk about the sort of periodically sorrowful delight, it feels like occasionally in there, it'll be the case that I sort of recognize like, oh, I spend a lot of energy. What a relief to notice that maybe you don't have to do that. Maybe you don't have to do that.

Katherine May:

And that's a very bittersweet feeling, isn't it? Because that sense that we... Loads of us, so many of us just waste huge swathes of our life in this obsession with why we're not getting everything exactly right. I know I've done it. My god, really. Wow. I've committed some... If I'd committed the hours to that, that I committed to, I don't know. If I approached my learning of Spanish on Duolingo with quite the same fervor, I would be great at it by now. However.

Ross Gay:

Right. Yeah. Yeah, yeah. That's right. That's right.

Katherine May:

But that puts me in mind of, I think one of my favorite parts of your book, which is right towards the end, when you're moisturizing your shins. And it struck me really hard as something I'd not heard a man write about before, not the act of moisturizing, but the sensual experience of being in a male body in a way that isn't violent or aggressive or sexualized unnecessarily or hard. The softness of being male, we don't hear about that.

Ross Gay:

I know, I know, I know. It's such a sorrow that we don't hear about that and that we're often compelled not to express it or to withhold that very obvious part of ourselves. Yeah, what a loss, what a loss. And also, what part of a loss I think is, requires that we inflict all kinds of damage on other people. When you can be like, hey, I'm soft, I'm tender, I'm hurting, in my experience anyway, that helps me not defend, not defend and then defending being all the other things, stupid and violent and brutal.

Katherine May:

Yeah. And not building a wall against other people's hardness that then creates your own hardness. I think that's the hardest act to pull off in adult life actually, is refusing to harden no matter what goes on.

Ross Gay:

That's it. And part of that thing of growing up of sort of pulling into our... Mastering the world and losing wonder, losing enthusiasm, like giving away those things to sort of pretend to kind of enoughness or something. It is a kind of hardening, it's a hardening. And it's like, it's so sad. It's so sad. And it does, it feels like such a relief when we can let that crack a little bit. I'm inclined to read that essay. It's not that long. Do you do that all?

Katherine May:

Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Why not? Have you got it?

Ross Gay:

I have it.

Katherine May:

Oh, that would be amazing. Yeah. I love the sound of pages being shuffled through the ETHER. That's a delightful thing.

Ross Gay:

Okay. Yeah. It's called Coco-Baby.

Ross Gay:

I caught sight of myself this morning in the mirror applying coconut oil to my body. I was bent over with one foot on the edge of the tub, rubbing the oil into my calves, which had become a particularly ashen part of my body, particularly visibly ashen as it's summer, which I'm trying to address with a loofah and the oil, abundantly applied. If you want to get way further into this, and I think you do, I recommend Simone White's essay "Lotion" in her book Of Being Dispersed. This time of year I am mostly brown, except for the stretch from my waist to my mid-thighs, which is a lighter shade, neither of them to be compared to a food or coffee drink. With my leg up like this, bent over, my testicles swaying just beneath my pale thigh...

Ross Gay:

I can't help but interrupt myself. I got to interrupt myself for a second. I once made the interesting choice to read this essay at a huge poetry festival, where there were like, I don't know, there might have been 800 high school children in the audience.

Katherine May:

Oh my god.

Ross Gay:

And I swear to you, I don't know what... Because I think the spirit, as your listeners will know, when we get to the end of the essay is the right spirit. But these 16-year-old kids, when I said testicles, they were like, "No!"

Katherine May:

Oh, I bet that was a great moment. [inaudible 00:42:06]. I bet that was a delight in itself.

Ross Gay:

It was wonderful for me, but they were like, uh-huh. I don't know if they're ever going to read another thing.

Katherine May:

Love that. Continue.

Ross Gay:

With my leg up like this, bent over, my testicles swaying just beneath my pale thigh-

Katherine May:

Ah, sorry, do that sentence again. I just knocked something off the table. I'm sorry. I'm so sorry.

Ross Gay:

Your pencil was like, ah.

Katherine May:

Sorry.

Ross Gay:

With my leg up like this, bent over, my testicles swaying just beneath my pale thigh, I wondered if, whenever I'm in this position, which is often oiling, cutting toenails, I will always think of Toi Derricotte's poem in The Undertaker's Daughter where, as a child, she walks in on her abusive father standing more or less just like this, though he's shaving. Seeing his testicles dangling like that, she thinks they're his udders. As she writes, "The female part he hid, something soft and unprotected I shouldn't see."

Ross Gay:

I watched myself rub the oil liberally on my body while I was still wet, which my dear friend recently taught me keep some of the moisture in. I got my calves, then my feet, lacing my fingers into my toes. When doing this, I often recall another friend who, watching me put lotion on my feet one day smiled and said, "Good job." Up to my thighs, inner and outer, around my ass, which seems to want to break out some when I'm sitting too much. Then I get both arms and shoulders, my chest and stomach, and what I can reach in my back. Usually I oil my face with the residual oil on my hands, and finish by oiling my penis, not always last, but often, which I wouldn't read into too much, one way or the other.

Ross Gay:

Today when I watched myself, particularly when I was oiling my chest and stomach, which I do kind of by self-hugging, I was thinking how many bodies of mine are in this body, this nearly 43-year-old body stationed on this plane for the briefest. I could see as I always can, probably kind of dysmorphic-ly, my biggest body, when it was 260 pounds and a battering ram and felt sort of impervious. I could also see my 12-year-old self, chubby and gangly and ashamed. And of course the baby me, who I don't remember being, though I have seen pictures.

Ross Gay:

When you watch yourself in the mirror, oiling yourself like this, wrapping your arms around yourself, jostling yourself a little, it is easy or easier to see yourself as a child and maybe even a child you really love. It is easy, if you decide it, which might be hard, to let the oiling be of the baby you. Or at least I thought so today, looking at myself, whom I am so often not nice to. But the baby you, you oil until he shines.

Katherine May:

Oh, that's so perfect. Thank you so much. And I have to say, I love that my first male guest managed to talk about his penis and his testicles. I feel like we've done the whole thing. Yes. I feel like I've achieved a full cycle now and I've done it and I'm feeling really good about it. Ross, thank you so much. It's just been such a pleasure to meet you and to have you on the podcast. I'm so thrilled you said yes.

Ross Gay:

Thank you.

Katherine May:

Yeah. Thank you so much.

Ross Gay:

Thank you. It's really great to talk to you.

Katherine May:

Welcome back. I hope you enjoyed that. While I'm standing here, and I will admit I'm getting slightly wet now, but I don't mind, but I'm looking at my tree, my only fruit tree in my garden. I have a very small garden. And when I first moved in, I planted a green gauge tree because I wanted a tree. I couldn't have a big tree, but I also wanted something that I could pick fruit from. And green gauges seemed to me to be very essentially Kentish really. They're a small green plum, but they're intensely sweet and you don't see them in the supermarkets very often. You sometimes see them in the green grocers, but they're actually, as it turns out... Thunder's still going. Oh, it's a good one. It must be nearly right overhead now.

Katherine May:

They're actually quite hard to grow, the greengages. It took 10 years for my tree to fruit and now it's fruiting every year. I've learnt to feed it with seaweed feed and it seems to help it a lot. And it actually grows like crazy, this tree. I had it pruned by someone else last year, because I was too scared to do it myself and already it's looking really straggly. It seems to have a lot of determination to get on with the business of producing fruit. And I think I've got a great crop this year. They're small at the moment, but they're all over the branches.

Katherine May:

And the trick with greengages is to not catch them too late. They go off really quickly and the wasps get them. So I'm going to be keeping a close eye on them this year. I might make some jam. You never know. Some really good green jam. Anyway, that's today's delight. And of course, the thunder and a bit of lightning, but less lightning than thunder without a doubt. I think it's beginning to pass now because you can hear the seagulls coming up in the air again. They seem to know when it's all over. They're really good predictors of a storm because they come in from the sea.

Katherine May:

I hope you enjoyed that conversation. I just wanted to say thank you to Ross again, for making the time to chat to me as a man without a iPhone smartphone, I should say, he gives me the sense that maybe he's not too bothered about getting onto podcasts and people's Instagram feeds and all the things that I fuss over in my daily life. So I was really, really chuffed when he said yes. And thank you to all the people who suggested him to me and who said that I really must make him my very first male guest. There will be more. I need to keep up the habit. I'm actually going to be taking a little break over the summer. More thunder. I hope no one here is not enjoying the thunder.

Katherine May:

I'm going to be taking a little break over the summer from producing new episodes just for a few weeks, just to rest and reset. I'm going to be visiting America for the first time since Wintering came out. So I'm hoping to maybe see some of you there. I'll let you know about anything I'm doing. The rain's getting harder now. And I'm also running my first retreat, which you may well have heard about, but if not, do have a look on my website to learn more about it. And all of those things are going to be keeping me really busy.

Katherine May:

And in fact, it just gave me the opportunity to do something that I wanted to do for ages, which is to put some of my earlier episodes into the very able hands of producer, Buddy, to kind of remaster them a bit and to get them back into shape because I produced the first series and you can really hear the difference. My guests were amazing and I feel like I didn't do them all justice. So I'm hoping for some slightly crisper versions and maybe for those of you that have only started listening more recently, there'll be a really nice surprise because there's some awesome people back there in the past.

Katherine May:

Thank you as ever to Meghan and to Buddy for looking after the podcast so well, and to my Patreons. This month, they have been formulating questions for all kinds of interesting people, including Susan Cain, which I think they really enjoyed. And we also had a lovely live Q&A about living a creative life, which made me dig so deep to think about how I think about my own practice and how to make it sustainable. I think I get way more out of this experience than they do. Ah, the robin has come to see me in the greengage tree now, which feels like a lovely time to say goodbye, because he and I are buddies now, we're mates and I've got some bonding to do. I'll see you all really soon. Bye.

Show Notes

This week, Katherine talks to Ross Gay about finding delight in dark times.

Ross’s practice of writing down a daily delight - a small surprise or pleasure that might otherwise go unnoticed - is the foundation of The Book of Delights, his bestselling essay collection. Here, he talks about the way that delight can sit alongside our fear, anger, frustration and grief, not to block them out, but to find a way to survive them. Along the way, we touch on fleeting moments of human connection, the joy of tending a garden, and childlike art of noticing.

In a first for The Wintering Session, Ross closes with a beautiful reading that meditates on the softness of living in a male body.

We talked about:

Fleeting moments of human connection

The joy of tending a garden

The childlike act of noticing

References from this episode:

Ross’ website

Ross’ book: The Book of Delights

Toi Derricotte, 'The Undertaker’s Daughter'

Please consider supporting the podcast by subscribing to my Patreon where you’ll get episodes a day early (and always ad free) along with bonus episodes and more!

To keep up to date with The Wintering Sessions, follow Katherine on Twitter, Instagram and Substack

For information on Katherine’s online writing courses, including her programme Wintering for Writers, visit True Stories Writing School

Note: this post includes affiliate links which means Katherine will receive a small commission for any purchases made.

Wintering is out now in the UK, and the US.