Kate Fox on on the potential and power of poetry

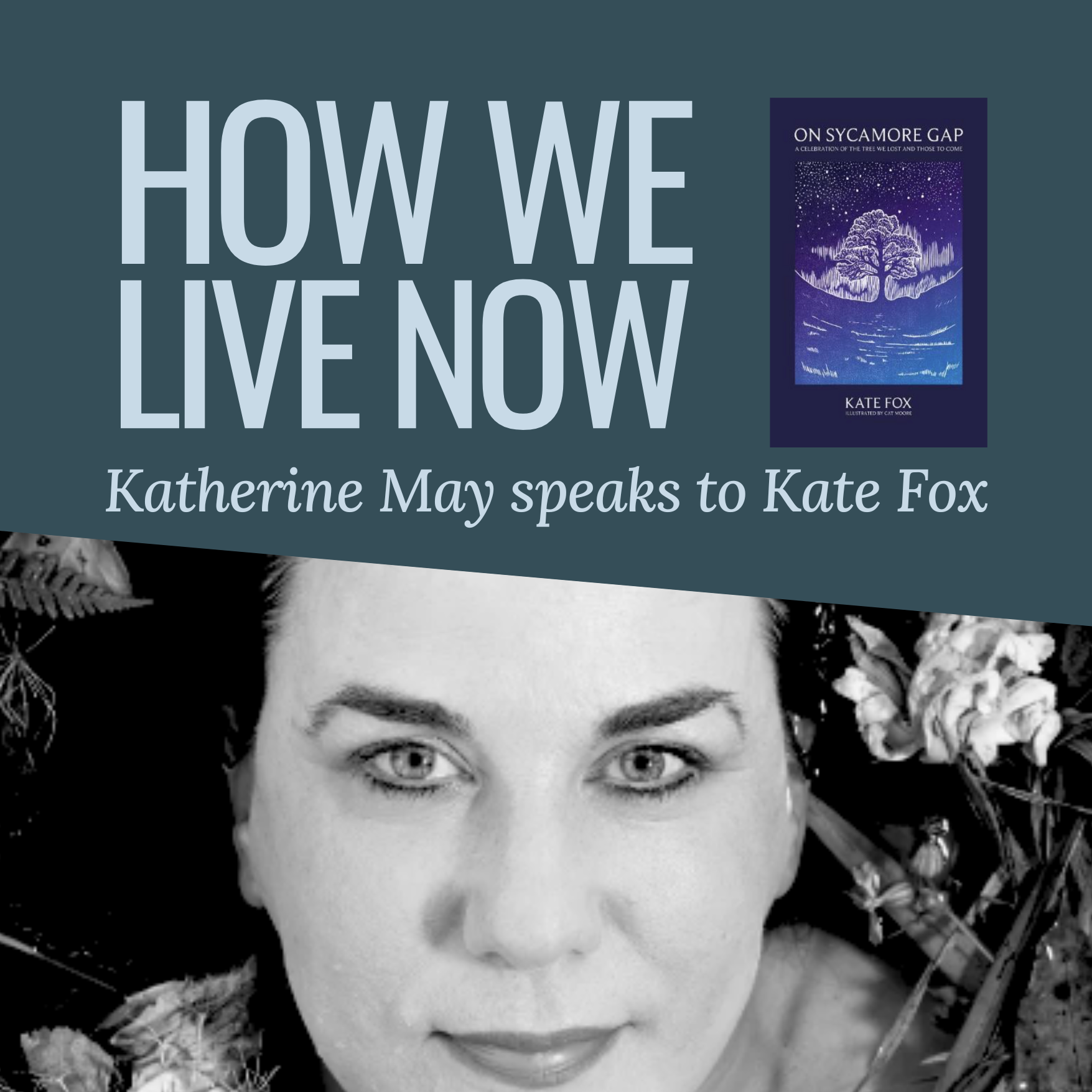

How We Live Now with Katherine May:

Kate Fox on on the potential and power of poetry

———

It was National Poetry Day in the UK earlier this month and Katherine talked to Kate Fox about her new book, On Sycamore Gap, in an extra Book Club event. Kate’s book is about a very special tree in the north of England that was chopped down by vandals, but that has brought people together in the aftermath of its felling.

Listen to the Episode

-

Please note, this is an automated transcript and as a result

there may be errorsKateFox_Substack

Katherine May: [00:00:00] Hello, Katherine May here. This is a live recording from the True Stories Book Club, which we organise each month on The Clearing. This month's guest is Kate Fox, who joined me on National Poetry Day to talk about her new poetry collection on Sycamore Gap.

Katherine May: Welcome and happy National Poetry UK. I'm just going to make sure that, um, the webinar chat works and I think hopefully it is. Um, I am really thrilled to welcome Kate Fox to see us today to talk about her fantastic new book On Sycamore Gap. [00:01:00] Beautifully modelled here. We will dig into more details, but you may know Kate from her other poetry collections, of which I'm such a fan.

Katherine May: You may know her from here on Substack, where she writes a great, great letter about neurodivergence, which I hope we'll be able to talk about. Um, and you may know her from Radio 4's The Verb, where she regularly broadcasts about poetry. So, um, yeah, she's a, she's a wonderful friend of mine and, um, I know you're all going to really enjoy hearing from her today.

Katherine May: I need to pull her up onto the screen now, which I'd love to be able to do quietly and look competent, but I've yet to manage that, so I'll have to talk about it. Here we go. Um, and hopefully, In just a couple of seconds. There she is! Hi Kate,

Kate Fox: welcome. Welcome. That was very physical as a virtual process, that was down there.[00:02:00]

Katherine May: It is quite strange, isn't it? I've never got the hang of, um, this feeling of like dragging someone into the room. It feels a bit like, you know, I'm a psychic medium and I'm conjuring you up. Yeah. Okay. How are you today? We've, we've been backstage chatting. Um, how, how is life landing on you today?

Kate Fox: Uh, today I am in a Low level, impending burnout, it feels like, um, because I'm busy with the book launch and a show, but it did go on a, we've got in the northeast of England today, one of those beautiful, um, Autumnal days, got the sun with that edge still of warmth in it, and the light was beautiful, low yellow light, and I walked, I had about an hour and a half walk, um, partly along the sea, and I was thinking, oh, this is nearly, Nearly [00:03:00] properly relaxing, like, for the performance it was.

Kate Fox: So that is really nice.

Katherine May: Yeah. Oh, I'm glad for you. Um, yeah, we have the same kind of day today. It's been really beautiful. I managed to get out to walk the dog, which the dog is always grateful for, obviously. And just now, actually, as you were saying, what a lovely day it is. I looked out and I can just see the moon through my, my window.

Katherine May: So, oh, is that the moon? Oh no, I'm lying. That's a cloud. Oh God. This is all going wrong. That's not the moon at all. As I looked closer, I was like, no, that's the wrong shape. I can't see the moon. Basically, I'm like, things.

Katherine May: For people who are here, I think, um, I think the chat should be turned on. So please say hi if you're here and tell us where you are here from. Um, I will be taking questions for Kate a little later. And, um, Oh, no, no, it's not. So somebody, okay, let me try that again. [00:04:00] The questions are obviously working. Um, Okay, does that work?

Katherine May: Ah, here we go. Attendees can chat with everyone. Right, so now please do say hello. Um, I have, yeah, there's too many variables on these things. Hello, there you go. The chat is working. Um, yeah, please, please feel free to say hello and tell us where you are. And if you have a question for Kate, that you can use the Q& A box.

Katherine May: Um, and we will, we will gather questions together for the end of the, of the, uh, hour, um, and ask them all in one go. Um, Kate, would you like to start us off by maybe telling us like a little brief introduction to the book and maybe reading a poem or two for us?

Kate Fox: I will. Thank you, Katherine. Um, I was asked to write this poem, actually, by the publisher Harper North over the summer.

Kate Fox: I think they had realized, as I It feels like a shock. [00:05:00] It's nearly a year, and in fact, it has just now been a year, September the 28th, that the tree at Sycamore Gap in the northeast of England along Hadrian's Wall, um, was cut down in the early hours of the morning. Something that just was felt as an absolute shock and a grief and a disbelief that reverberated around the world.

Kate Fox: I know I saw it on social media, and I just, I was, I had to check, had to check multiple sources. I was like, and You know, here in the North East, and I know far beyond, but I've sort of been talking about it a lot with people over the last few days. That grief is still very visceral, very felt. Um, although for me, actually, and it's, I suppose, is it testament to the, the potential and power of poetry and writing?

Kate Fox: I feel like through the process of writing these poems, it's just a little poetry book, it's kind of, um, but it's, you know, [00:06:00] 12 minutes or so worth of poems. Um, and crucially visiting the site. So I have kind of moved from this grief to a A very hopeful place. I genuinely, I feel hopeful about all sorts of things.

Kate Fox: I feel hopeful about the way that people now are, where the stump is, because they come and they openly grieve. and are hopeful, both. Now, we've been through so much as a world in the last few years, I know we still are ongoingly, and there's a lot of unexpressed grief, and to see a memorial site where grief is open, for starters, healthy, I'm feeling good, but as I say, with hope as well, because when I went in the summer, uh, there was a sign that says the stump, no, the tree, this tree is alive.

Kate Fox: And then we got news at the end of July. It's sprouting. You can [00:07:00] actually see the green. And when I went back last week on the anniversary, you can, the leaves, they're sycamore shaped leaves sprouting all over. So there's that hope, that renewal, you know, it's, it's both. But then there's the wider conversations that are now happening at the Sill, the visitor center nearby.

Kate Fox: They say they can talk more openly to people about the The ecosystem difficulties. Yeah, the challenges of kind of maintaining it. The challenges, absolutely. If you went to National Park, you know, there's a, I mean for starters, there should be lots more trees there than there are actually. And I've come to, so I feel very mindful and I'll get on with it, but I know this is fascinating.

Kate Fox: Well, I feel very mindful of, ah, people are still in the brief space, especially if they haven't been to the site, especially if they haven't started having these conversations. Um, I know, [00:08:00] I feel like it's, to me, it's more, It's truthful, it's a very truthful place. That's, it made me think of my favourite quote anyway, Leonard Cohen's, There is a crack in everything, that's how the light gets in.

Kate Fox: Um, and that stump, that growing, alive, still beautiful to me, stump, in that very beautiful, uh, hollow on Hadrian's Wall, it's, it's a broken symbol, But it's powerful. Visitor numbers are not any lower than they were before as well, which is great. That's

Katherine May: great. So people, yeah, I wonder if, I wonder if it's easier for, you know, it's more tempting for people to come now, like they're coming for a focus.

Katherine May: And we, we have not had that, that national moment of grieving after COVID. Like there is, Massive loss in the air, trauma, pain, hugely changed lives. And yet we've not [00:09:00] had that focus. That's really surprised me. And it's so interesting to hear you say, well, actually here is a place in the North that feels Northern specifically, and that has that kind of quality of Northern ness that matters to people, uh, that, that they're coming to, to express, to let that, that, that come out.

Katherine May: Yes. Extraordinary. Yeah, so

Kate Fox: shall I, I'll just, I'll do the poem that's at the end of the book, which I've realised is where I should start when I perform from this book. Um, okay. So, and I, just to explain, there are six sections that are done in a kind of ballad form. Four lines. very rhymy, very rhythmic, because on the border between England and Scotland, um, there were, for years, many raids, battles, and family feuds, and border ballads.

Kate Fox: commemorated [00:10:00] these. So it felt like the border ballad was the clear form for, um, a tree poem, but that forms the trunk of this book. Um, and then there are little branches in between of haiku poems and sonnets and different forms. So, but this is the final piece of the trunk. Even as gap rather than sycamore, it is somehow as present as it was before.

Kate Fox: Not just as picture. Or as regret, but as buds of new growth, with more blossoming yet. And there is the power of intention, after carelessness and slaughter, to bring back the birds, to purify the water, dreams yet to manifest. Of more regeneration, Fueled by something as real As wild imagination. Nothing's ever forgotten, Nothing is ever destroyed, [00:11:00] Memories can be rekindled, Relived and re enjoyed, There's days out still to come, Proposals, picnics and plans, Walks yet to be taken, Through the breach that it still spans.

Kate Fox: We can render the opposites. Both at once true. Something destroyed can also renew. There once was a tree, now it is gone, and in more ways than we know, it is still living on. And I'll just do a branch bit that maybe talks a bit more about the ways in which it's still living on, apart from in memories.

Kate Fox: Ideas, Reflections. We also have this wonderful body of work now, um, from all sorts of sources about how trees and fungi are connected under the [00:12:00] ground. Their roots connect to, well, everything, but really, I think we thought, oh, a tree, on its own, it's just a tree. And we now know that there's the, the wood wide web, the idea of trees communicating in forests.

Kate Fox: We know that, um, the mycelium of fungi are, uh, an amazing network of connection. So this poem in the middle of the book, I'm going to kind of read it twice from bottom, no, from the top down, from the crowns to the root. And then you'll hear the same lines from the root to the top. And the meaning should change.

Kate Fox: It's a palindromic poem. As above, so below. I was just wondering. Never think that I was an extraordinary tree, the tree of life. I was an ordinary tree. It's not the case that my roots link me to everything [00:13:00] else in an interconnected system. Like a brain sparking electrical currents, my growth functioned wisely.

Kate Fox: Like everything else in nature, I am sovereign. So don't believe that my death will travel beyond itself, that roots are the whole world, as above, so below. Fungi, soil, insects, birds know I was just an ordinary tree, if you look at the world from the bottom up. If you look at the world from the bottom up, I was just an ordinary tree.

Kate Fox: Fungi, soil, insects, birds know, as above. So below, that roots are the whole world. My death will travel beyond itself, so don't believe that I am sovereign. Like everything else in nature, my growth functioned wisely. Like a brain sparking [00:14:00] electrical currents in an interconnected system, my roots link me to everything else.

Kate Fox: It's not the case that I was an ordinary tree, the tree of life. I was an extraordinary tree. Never think that I was just one tree. That's

Katherine May: so clever. How did you do that, ? Well,

Kate Fox: basically I looked at other pal, pal, poet, how they work, particularly Brian Stein's refugees. I went, oh, and it was a bit of a crossword puddle situation.

Kate Fox: It was very satisfying, the puzzle of it. So once I'd had the idea of crown roots, crown roots, I, it was satisfyingly. Yeah.

Katherine May: So smart and so, so wonderful. Um, I, I'd love to sort of kick us off by really asking about like what your relationship with the tree was before you were commissioned to write these poems because for me it was a [00:15:00] really interesting moment that I have never been to, I've never been to see the tree but as soon as I saw it in the news I knew it.

Katherine May: I realized how many times I'd seen that picture and felt like a connection to it even though I'd never been there. Did you have a more personal relationship?

Kate Fox: Yes, although I have to say I feel like not as personal as a lot of people, people in the North East who would go there and maybe there were proposals under that tree or they would take their children there, having taken their, being taken there by their parents.

Kate Fox: Actually, my strongest memory of the tree is going there during the pandemic. And it was when you couldn't travel far out of your local area, and on a particular day, there was, there was just a line of people, like a line of ants going up and down Hadrian's Wall, and when kind of stopping at the tree, it was February, there were no leaves on it, and I did have this very clear sense, as [00:16:00] I do with the sea every day, I live near the sea, it was the same thing of, oh, thank goodness.

Kate Fox: This is here. This is here. This is still here. This has always been here. It will always be here. There was that sense, a very strong sense of that. I, but what is interesting, memories function backwards as well, don't they? When something happens, it can rearrange your memories so that they all kind of click, clack, clack.

Kate Fox: And Although I have that very strong picture of, because there is so much photography of, isn't there? Particularly with Northern Lights or Big Skies. There's stars and yeah,

Katherine May: Milky Way behind it and that kind of thing. Even a

Kate Fox: sense of space and expansiveness. But I've been thinking a lot about when I first came to this, area of, of England, the North East, back in 1998.

Kate Fox: And it was just as the Angel of the [00:17:00] North, another icon of the North East, was being, it was about to be erected. So you were about to have two massive lorries with two huge pieces of sculpture of Antony Dornley's body going up the And before they came, The people in the North East were saying, well, this is ridiculous.

Kate Fox: Like, why are we having a big sculpture, sculpture of an angel on the motorway? What? This is just, complaints in the local paper, general annoyance. I was a radio journalist at the time, even worked on a story about how the angel of the North seemed to be modelled on Nazi statues, uh, from the early 1940s, because, you know, it wasn't modelled.

Kate Fox: But anyway, the minute it went up, There was just this swelling of pride, absolute pride, and it almost was like that. It was like, oh, everyone's looking. This is a, this is special. This is, this is different. This is, [00:18:00] we are notable. We are marked. Our, our mining history, it's on top of a mineshaft, is transformed, transmuted.

Kate Fox: And actually, The tree is more similar to that as a symbol than you would think, in the sense of ancientness. It's, it wasn't until, After 1991, when the film was in Prince of Thieves, the Steve Costner film, and there was a geographical, uh, uh, what's the word? Yes, anomaly. Anomaly, yeah, where basically they went from Dover, not to Dover, To Adrian's wall, ooh, and then Jimmy Costner's on his tree, and Morgan Freeman's there.

Kate Fox: And still at that point, actually, that did not immediately make the tree iconic. It was then in Brian Adams Everything I Do, I Do It For You. And even then, it took a few years before digital photography and [00:19:00] those beautiful northern lights made the tree a symbol, an icon. And I, I It's really interesting.

Kate Fox: People would come down to the stump site and be saying, It's an ancient tree, Sagefly. It's almost a hundred years old. Five hundred! And you know, pedantic me wanted to say, I think you'll find it's actually about a hundred and ninety years old. I didn't want to hear that because it feels ancient and that's important.

Kate Fox: I think it's become In a de industrialised area, a really important symbol of nature and the touch, um, but actually that is happening in an area where nature is being touched. It's being touched quite a lot and often not in a good way. Um, so although, I don't want, I absolutely don't want to reduce, because what this tree stands for as a symbol, which feels almost [00:20:00] like a religious symbol in a secular age, really, it's, it's helping us remember some things, seems to be helping us forget, or was helping us forget some things, and it's not.

Kate Fox: Those things are wide open and exposed. And it's, and again, that's why I have a real hope about if people were very conscious around, um, what that feld tree means, there's a real opportunity for transformation,

Katherine May: actually. I wonder if they even realised it meant anything to them at all until it was feld, actually.

Katherine May: Um,

Kate Fox: well, I, yesterday, oh, well, no, that's a good point. I thought you were going to say before it was, so before the Robin Hood film, there was a very down to earth farmer, uh, who, who is from that area. And he was saying, well, it used to be known as Clayton's Gap before it was Sycamore Gap. I was like, oh, right.

Kate Fox: And I said, and I felt like I knew the answer, but I said, and did the, you know, did the tree have a [00:21:00] meaning then? You know, what, what did it mean? And he just went, no.

Kate Fox: And it's interesting, it was invisible. It was not, I mean, it was, it has always been a very beautiful scene, a beautiful tree in a beautiful spot, beautiful landmark. But it was. Interestingly, it took the outside to notice it. And there are so many places like that, I feel, aren't there? Where a place, a region,

Katherine May: doesn't

Kate Fox: see itself until it's seen from the outside, almost kind of needing that external validation.

Kate Fox: And then that activates a pride, a pride which has often been lost because of what else has been lost in that region. And so it's, I think, and identity in many ways, that it's been felt as a horrible blow to an already, um, uh, What's the word [00:22:00] be? Be denuded area. Yeah, yeah.

Katherine May: Be good

Kate Fox: beard place. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Kate Fox: I think what it means inside and, and outside they, they are different things. I think that's

Katherine May: interesting. I mean, I like, as you were saying that, I was thinking, you know, my own town, like living in Wibo when I was a kid, it was seen as a really kind of grotty kind of forgotten place. And then we had, I mean, I think we had like various people coming down to eat the oysters and that.

Katherine May: That kind of made everyone feel like we were special. Um, but also there was Sarah Walter's Tipping the Velvet, which romanticise Whitstable in this really radical way. And loads of people move there because of that book and the, and the TV series. Yeah, lots of, lots of gay couples actually. It's really lovely, like lots of lesbians came and lived here, which of course has made the town lovely because, um, you know, take great care of the place.

Katherine May: Um, but it's, but it [00:23:00] also fills the, fills the whole town with people who feel joy at being here. And And then this pride, you know, came really fast and it's Yeah, in my lifetime, it's changed enormously. It's now seen as a nice place to live and it did not used to be seen as a nice place to live at all when I was coming here as a kid, you know, to have fish and chips and paddle on the shingly beach.

Kate Fox: Right,

Katherine May: yeah. It's so funny

Kate Fox: how that applies. With some of those, you know, nature, the natural, as if, as if, ah, well, these things definitely have always been there and they've always been just like that.

Katherine May: That

Kate Fox: sometimes, again, can help us, help us forget, well, Think of a lot of human made stuff has happened to you.

Kate Fox: A lot of it, not very good. Think on everyone.

Katherine May: Our understanding of nature has changed so much so recently and also our understanding of heritage. I mean in, um, in the, my next door town, [00:24:00] Faversham, there was famously a whole medieval street that was knocked down in the 70s to build new houses. I mean, that's unthinkable now.

Katherine May: That's just absolutely unthinkable. And I was recently, um, researching the Medway Megalith. which are a series of, um, like, megalithic, uh, stone monuments, like long barrows, basically, and some other sort of stone arrangements that surround the River Medway, near where I live. And, you know, loads of them were just ploughed out in the eight, as late as the eighties, or farmers found one of the stones inconvenient in the middle of the field, so just took a dumper truck and, like, moved it to another field, you know?

Katherine May: And it, like, even in that short space of time, I mean, that's Absolutely unthinkable now that you would remove a 6, 000 year old stone monument, like, so casually. But we've really changed, and we often think we've changed for the worse, but we've started to seriously value symbols like that, our heritage. Um, it's, it's changed, and it, it's actually quite [00:25:00] heartening to, to notice that sometimes, I think.

Katherine May: Mm. So, you were offered this commission to write, a book about Sycamore Gap. What, how do you approach that then? Like, what steps did you take? Because you didn't have that long to write it. I mean, obviously it's only a year since it happened, so you couldn't have had very long. Like, what's the approach?

Kate Fox: I, to, first of all, to go there was absolutely the first thing.

Kate Fox: Um, and to listen to the voices of people who were there, really, and the things that they were saying. And that's, uh, I trained as a radio journalist originally, as I mentioned, and, and actually that thing of interweaving voices. And I absolutely, I love, I love doing that. It feels like you're able to focus on what people are saying and almost form it into patterns.

Kate Fox: Um, and of course I know a lot of people here in the Northeast and I asked them how they were [00:26:00] feeling. But then I had to, and then I was aware, Oh, I'm focusing on people. I'm doing that thing again. Hang on. Come, come the tree. Come to the tree. And, um, but again, that led me to, to the roots and the tree. The book is beautifully illustrated, have to say by Pat.

Katherine May: It's lovely.

Kate Fox: Yeah. And she's a, a lion or cook, um, printmaker. And we had conversations very early on. I'm sure the picture, actually, this is my, my favorite picture. Ah, yeah. That lovely one in the middle. And my favorite one. That one would've been the cover. It was quite important in both our thinking. It's a ghost tree, it's slightly faded out, and it's got the roots there.

Kate Fox: The thing is, the roots remained. The roots were, you know, obviously, the roots are, are still there and alive. I do think, I have to say, I kind of knew this wouldn't happen, but I would have loved if this was the cover. Because [00:27:00] for me, that is conveying that message of what you see on the surf, not all there is.

Kate Fox: Um, so that felt important. And so that image was, was guiding as well. And then I just, that idea of border ballads, um, thinking about the past, um, became important, helped me with the form. I mean there's a lot, I love, I love nothing better and I was unlucky, I had, I did have about three weeks where I could pretty much only have the poem in its big form, in my head.

Kate Fox: And I have to say, it helps. I live on my own. I don't have children. Uh,

Katherine May: I'm just being uninterrupted. Yeah.

Kate Fox: Yeah. I was single. That was the only thing. In the middle of it, I did get COVID for a week and that, and at certain points, That was, so, COVID very bad, I don't want to have COVID, um, for about three days it was very unhelpful because I couldn't focus, and then for [00:28:00] three days it was really helpful, so it really calmed a lot of brain chatter down.

Kate Fox: The rare gifts

Katherine May: of COVID, there's not many

Kate Fox: of them. Um, and so it was just all, it was weaving together, and I've been thinking about ideas of regeneration in my other work in a completely different context. I've been doing a show about Doctor Who and neurodiversity. Um, the publisher actually, um, Jen from Harper North was brilliant.

Kate Fox: She made that connection between the idea of bigger on the inside, which is an idea from the, the TARDIS in Dr. Who is bigger on the inside, but way bigger on the inside. And she said trees are bigger on the inside. You know, said that idea fed in Mm-hmm. Also myth. Became important. I was also asking, what is the, you know, this is, this is not a neutral spot where the tree is.

Kate Fox: Hadrian's Wall, it's not a neutral spot. The Roman Empire, they came and invaded and there's Celtic tribes and they're all [00:29:00] sort of, they either get co opted or, you know, You know, Gentoff elsewhere, all killed and the Picts held back on the Scottish side of the border. Absolutely not, in any way, a neutral place, this.

Kate Fox: Um, and I'm really interested in it as a place of, well, it's violence. It's been a very violent place.

Katherine May: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Kate Fox: And I've sort of pulled some of that in and made the decision to not consciously, although I am, Absolutely intrigued. I cannot deny it by why some people cut the tree down. Yes, I kept thinking about it.

Kate Fox: I do think a lot of, two men are on trial on the 3rd of December. They've pleaded not guilty. A lot of what people have speculated around the what and the why seems intriguingly Potentially just wrong. And the journalist in me is [00:30:00] like, Hang on everyone. We actually don't know. Like we don't know and I'm not saying we shouldn't speculate.

Kate Fox: for a day, but we really don't know. But I wanted to make that link of the, the violence of the wall's history, of sudden change, of sudden collapse, of sudden chaos. This is not

Katherine May: overthrowing, like there's that whole overthrowing metaphor. Yes, yes, absolutely.

Kate Fox: This is in fact not, not a new thing

Katherine May: for this part of the film.

Katherine May: That's so interesting though, isn't it? That I hadn't made that connection at all and, and this. The crime behind it was so, so shocking and felt like almost every bit as violent as if the tree had been a person like that. And that was, you know, That's revelatory in itself, the, the, about our relationship with trees, our profound relationship with trees and how horrifying that, that act was.

Katherine May: But I think [00:31:00] one of the reasons why it's been such a big story and why we're still talking about it a year later is it's, it's impossible to make sense of it. You know, they, what, like the why. was just asking itself over and over again and it still is, it's still a mystery. I mean, wouldn't it be great if they could just tell us, like, if they're plead guilty and tell us, like, you're desperate to understand what the motivation was.

Kate Fox: I, um, yes.

Katherine May: Have you got a theory?

Kate Fox: I do have a theory. Uh, yes. I have two possible theories and I, and I'm not going to share them, uh, sadly, um, but I, but I, I mean, I will not, and I'm very intrigued by this and it's very surprising. Um, so a production company are making, uh, a two part documentary about it, which will air next summer.

Kate Fox: They usually make true crime and murder [00:32:00] documentaries and they were, they were They were filming on the day I was there. And yes, looking for footage, as they had said, you know, usually if there's a murder, you can talk to people's family and friends. And they were talking to people around the wall. And, uh, Northumbria Police, um, have, are cooperating with them.

Kate Fox: And I gather, in fact, slightly, I know we're going off and everyone's like, we can't just talk about the magic of nature and trees and stuff. But I'm like, actually, there's some, there's some wider stories here. Uh, Northumbria Police are cooperating with, uh, that documentary series. And, um, in fact, they've been.

Kate Fox: They've paid the police for their, um, for the story. And, um, there's a heck of a lot of very interesting and surprising stuff around what stories are told by whom, what we remember, what we forget. And again, people look at the [00:33:00] tree, that beautiful tree, and I have to say, so for me it stands for, and actually I should do another bit of poem maybe, it stands for all those other trees that are, um, You know, you walk around your neighborhood, there's a tree stump, someone's felled it, the council's just decided, oh, that's a bit inconvenient, or someone didn't like a tree blocking their view.

Kate Fox: This, I have to say, equally sends a slaughter of trees, it's happening. Obviously, the rainforest, it's happening everywhere all the time, and something is focused, you know, I would say, a great sense of loss and pain around the world. The natural loss that we're experiencing. Environmental grief, yeah. Yes.

Kate Fox: Is it Weird story behind it, I think. Very weird story. Is it any more vandalism than what your local council have probably just done to that tree over [00:34:00] there? I would say. There

Katherine May: we are.

Kate Fox: Can I?

Katherine May: So you're going to read a little more?

Kate Fox: Yeah, can I read a little bit of, get more tree in?

Katherine May: Yes, please.

Kate Fox: It was not a gentle time on earth, and the last thing anything, anyone wanted to see was the shocking gap in the sky 2023.

Kate Fox: A sinking in the chest, a hole, a wound left exposed, rumours whirling, senseless, destruction all over the news, the world's darkest shadows unfurling. When our security feels threatened, we need more than ever to hold the belief that the seasons will soothe all sorrows, we can always turn a new leaf. That day, a report had been published, while we were still grasping for words.

Kate Fox: A sixth of our species in danger of extinction. Drastic declines in animals, plants and birds. So, this tree [00:35:00] can still rise as a symbol. This tree, this single one for everything that we are losing for all the damage that we have done. The stump. A stormer that can speak of hope, and why we need to trust in our roots, to keep faith in what is not visible, just as unseen seeds can sprout new shoots.

Kate Fox: Let this tree stand for all the forests who are thriving or under threat, and for upholding the new tree charter, reminding us not to forget that we can all act as the guardians of the vitality that exists on this earth, replacing, recovering, replanting, embracing every living being's equal.

Katherine May: Lovely, lovely. And yeah, I think it really, it does trigger that, that feeling of environmental grief, that feeling that we know that some of it has happened already, but we know that there's more to come. And, and every day we're turning on the news and seeing [00:36:00] global destruction, you know, all of this stuff that's now happening that we saw coming.

Katherine May: And the, I think the grief is overwhelming sometimes, honestly.

Kate Fox: And actually, and again, that's why that stump site with its hook, with its giant sycamore blossoms going, yeah, you cut me down, but I'm a sycamore. I'm basically a weed. I didn't realize that. I mean, sycamores have great kind of, um, sometimes religious significance.

Kate Fox: They have spiritual significance, but also for your ordinary, I'm a tree expert. They're like, oh, stick them off. Just read, go on. Just spread its seed everywhere. It's a very hardy and resilient tree. It should never have been able to grow on the wall anyway. It's kind of, it's funny, I was quoted yesterday saying it was the perfect tree in the perfect place.

Kate Fox: In one way it was. It's a child's drawing of a tree.

Katherine May: Yeah.

Kate Fox: framed, it was planted there on purpose to be a [00:37:00] landscape feature. At the time of Capability Brown, who, you know, was all about the landscape features, and John Clayton, who was busy excavating the treasures of the wall because he wanted to preserve them for the nation, also seems to have thought, Well, do you know what?

Kate Fox: I won't see it. He selflessly thought. Bit more of that, please. I won't see it grow, but in 200 years time, this'll look bang on. And Kevin Costner will come along. He'll make a film. And, you know, Touched by the hand of Costner. Exactly. And, but without You know, without that, it would have been this little seen tree that was an important landmark, you know, for people, a way marker, thinking I'm nearly at the car park, or I'm on the military road, I'm close to home, there is that beautiful view.

Kate Fox: It wouldn't have been anything beyond that. What a selfless, brilliant act, and what a, a wonderful thing [00:38:00] now, again,

Katherine May: as

Kate Fox: how nature will just go.

Katherine May: Yeah. Right

Kate Fox: now gone. Anyway, thanks. Yeah, back on.

Katherine May: Yeah, it's a, it, it's actually a reminder that it's a great moment to plant trees if ever there was one. Um, guys, I'm gonna take questions for Kate in about five minutes, so if you have them.

Katherine May: Please write them in the Q& A box at the bottom of the screen, um, rather than in the chat because I find it really hard to find questions in there because it gets, it gets busy, um, but I would really love to take your questions in a minute. Um, Kate, this feels like a really neurodivergent book to me. It feels like you went deep into geeking out about trees as much as anything else.

Katherine May: Can you talk a bit about that connection? I know you write so beautifully about it always, but were you conscious of of thinking of it that way?

Kate Fox: Yeah, very much so. I mean, someone did say to me the other day, I never saw you as a tree poet, Kate. I was like, I know. What does that mean? [00:39:00] Actually, I have been writing about trees for a little while now, really as an analogy for neurodivergent people, the way that our roots underneath we're communicating, going, Oh, everyone else here is talking a lot at this dinner, um, you know, spotting each other and kind of sending out little signals of, of, um, care and connection.

Kate Fox: So, and that idea that, I mean, I don't honestly, feel the primacy of the human above all? Like, feel it? Yeah. Particularly, I'm a bit more like, okay. And it's a, however, conversely, I've also never been a, I, I, I haven't. Primacy

Katherine May: of trees person.

Kate Fox: No, I'm really a talk poet, really. And actually what I am seeing is just this interconnectedness.

Kate Fox: Of everything and this way of [00:40:00] looking this rhizomatic. I love that word. I love how people now are talking about rhizomes and networks instead of from the top down Um, and I think that's what I see. I also think it's lovely. It's interesting though, I'm having to, um, it's a challenge for me as a neurodivergent person whose emotional processing is sometimes delayed and it's sometimes really fast.

Kate Fox: I'm in a situation where I'm recognizing, for example, I'm in the northeast of England, a lot of people, for the tree is in a particular place. Am I, I'm, I'm not, I'm not there now. And I'm having to really feel into, okay, feel where people are. Know that you kind of really want them to go on this journey with you.

Kate Fox: Thanks for having me. to hope, because you can see it and you've felt this journey, um, you know, it can't [00:41:00] be rushed, or can it be rushed? Can poetry make it happen like a movie?

Katherine May: No, I mean, I think, I think what you do is you kind of create a medium through which people can feel their way in, you know, that they're, that you're, you're kind of seeding a network or feeding into a network that other people will connect to quite often.

Katherine May: I mean, I, It always surprises me the connections people make to my work that I hadn't thought about at all, but that's one of the loveliest parts of writing, isn't it? That people will take what you've said and make it theirs. I always find that a really beautiful process, actually.

Kate Fox: Yeah, yeah, yeah, very much.

Kate Fox: I have to say a lot of people as well have identified directly with The tree. They have felt they are the tree. A lot of people have had breakups, I have to say, have more than one have said, Oh, that tree, that's like our relationship. And especially if they had been, had visited the tree. Like, I mean, [00:42:00] actually, and again, that has then given them, given them that sense of hope and connection.

Kate Fox: And I love how, I mean, being able to throw your empathy is, uh, I think humans have that skill. I think a lot of neurodivergent people perhaps particularly have that skill, don't you? Oh, yeah.

Katherine May: Well, and that I mean, I, you know, one of the things I notice about myself more and more is that I find it really hard to watch violence on TV or, uh, people being harmed and, and that extends to animals and certainly to trees, you know, and I, and there's that, that sense that when that body is injured, my body feels it too.

Katherine May: That's the, that's the connection. And trees do always seem like people to me. And I do. always talk to them. I've got, I've got certain trees that I chat to on my walk, you know, like,

Kate Fox: yeah, I love, well I, um, a while ago, so Donna [00:43:00] Haraway has this idea of, of, so it's the dogs as companion animals, and then a long while ago I had to write another poem about trees, and I coined the phrase, there are companion vegetation, and I feel that so viscerally now as I walk around them all, trees are.

Kate Fox: companions and they're with us and probably they're living in a different time frame. Their time is different and time to ours is kind of thrown out of the trees, seeing us whizzing about, rushing about, not taking the mind of you. That's the

Katherine May: other

Kate Fox: thing. Which

Katherine May: is a true relation, a true representation of what we get, what we do.

Katherine May: Exactly,

Kate Fox: exactly. So to be able to take that more deep time perspective, I felt like, I mean, the As Above, So Below poem that I read earlier is the only poem I wrote in the voice of the tree. I didn't want to presume to speak for the tree who does not, after all, generally speak in human words. Um, but [00:44:00] I, I wanted to take that, that wide, you know, they, they, They've been here a lot longer than us.

Kate Fox: Oh, whoever, whatever particular force fell to that tree in that moment, they've seen one.

Katherine May: Before we run out of time, I just, I want to get you talking about your brilliant sub stack. Um, because you've, you've been busy actually the last year, you started a sub stack and a podcast as well. Um, interesting to see you turning really directly to neurodivergence in your work.

Katherine May: Can you talk a bit about that? Because, you know, it's always been in there for a long time, but it feels like you've got a bit of a mission at the moment.

Kate Fox: Exactly, it's a mission, and essentially over the time of the pandemic and the lockdowns, I lost all sense of direction. purpose and mission and future, very much, and just didn't have it.

Kate Fox: I was like, I don't really care about writing. The poetry world is all very silly. I was [00:45:00] disconnected from everything, partly in a PTSD way, I think.

Katherine May: Yeah.

Kate Fox: And then a year ago, I did a version of my Neurodivergent show, Bigger on the Inside, at a theatre to help launch the local theatre. And the audience that came were different than they had been before the pandemic.

Kate Fox: It was those late diagnosed, mainly women, um, but late diagnosed adults with ADHD, autism. It was the kids in schools who had been brought by their parents who were saying it's really hard to get the accommodations they need in school, but it's so good that they're represented. That reignited something within me and it took a little while for the flame to kindle because I've had this absolute fear of burnout, but I realized, okay, I just need to get on with it, with it, with a sub stack.

Kate Fox: You know, I've been really inspired by yours, Katherine. I've been really inspired by what you do. Some great

Katherine May: ones out

Kate Fox: there. Your building. Yeah, absolutely. I can see all these communities [00:46:00] and I've just thought I'll go for it. Um, so I've done that and then one of my audience Um, from that show, Nick King, uh, came up to me afterwards and we chatted.

Kate Fox: She runs a scheme called Neuro Bears, which it's like an online course, getting kids to understand and positively celebrate their neurodivergent identity. So bears, because you look at like pandas, bears, all different types of bears. They're all different. different types of, you know, they're just different types of bears.

Kate Fox: One's not better than the other. And that's a really lovely metaphor. It is, isn't it? It just works beautifully. And I think it works with trees as well. You know, biodiversity obviously is what New York diversity, the concept came from, but there's not a hierarchy of trees. Not really. It's like, Oh, you need a signal.

Kate Fox: You need a latch. You need a willow. Anyway, I had, I would not have started a podcast on my own. I felt like my perspective alone is too narrow, but the two of us, and Nick is, she has [00:47:00] kids, she's in a family, she works with young people, and I feel like that's the area I have so much less to say about, but it's very important.

Kate Fox: We've just clicked, and so it's called Neurotypicals Don't Juggle Chainsaws. She's from a kind of circus family, and she feels she's got neurodivergent privilege because, you know, circus carnival people, they're always going, just be you, be weird, be eccentric, you know, like if you come from an engineering family.

Kate Fox: And I feel like I have quite a lot of neurodivergent privilege by way of being a poet, being a words person, having

Katherine May: poetry.

Kate Fox: Very eccentric. Although at the same time we are both undergoing that ever complex journey, as you know, of unmasking and de masking. Yeah,

Katherine May: which is so complicated. Tell people the name, oh somebody's put your, oh no, tell me, tell people the name of your substack as well so they can find it because it's so complicated.

Katherine May: Not always easy to find.

Kate Fox: It's called bigger on the inside. So everything at the moment is called [00:48:00] bigger on the inside, bigger on the inside. And I'm, I'm trying to write, um, either every other week or weekly about some, oh, I've just recently realized quite a big thing though. At first I was still, I will do this, Because there's neurotypicals, I need to explain us to them.

Kate Fox: And now I'm like, no, I don't, I don't care. Well, I do care probably, but it's about us, the neurodivergent people, finding a space, finding communities, finding ourselves. And I don't want to write for the neurotypical gaze anymore. That's

Katherine May: exactly

Kate Fox: how

Katherine May: I feel. But I also, I also think, as you sort of alluded to, that, that challenge of, learning, not necessarily not to mask because I, you know, it's a real privilege to be able to mask when you need to.

Katherine May: Um, and I, I'm grateful for that, but learning, learning to notice when you're wearing the mask, um, is an ongoing process for me that I'm not always conscious of [00:49:00] the difference. And I, and I kind of struggle with that. Um, and also that's like linked to that is the challenge of managing energy, which you've talked about, and you've, you know, like, not sure how to not get burnt out.

Katherine May: Um, and that's, that's such an ongoing process for me of figuring out how to, I don't know, like, how to find balance without squashing down the really good bits of, of overthrowing yourself at stuff, you know, if that makes any sense. Like I, I'm grateful for my ability to hyper focus sometimes, but I also know that I can get really worn out from it.

Katherine May: And I'm, I'm still working on that.

Kate Fox: Yeah, exactly. And I suppose at least, you know, I mean, I often use hyper focus as a way to attempt to recover from a lack of energy, which has this [00:50:00] vicious circle of, oh, but now I've hyper focused on a really interesting conversation so that I can forget that I'm being sensorily overwhelmed.

Kate Fox: And that has taken even more spoons that I already didn't have. How do I balance that? And I wanted to have that conversation. Feels like progress to me, though, to be in a space where we're at least not, uh, capitulating to the capitalist system that says burnout is just normal. Like, go beyond everybody in the service of the capitalist gross machine.

Kate Fox: And once you've or,

Katherine May: or burnouts your personal failure, that's the one that really gets me. Of course. Yeah. Which is one of capitalism's

Kate Fox: big lies, really to, yeah. It's all right folks. Just go to a lovely massage at your workplace that they've laid on for you so you can be resilient.

Katherine May: I'm stabbing myself in the head with a pencil now.

Katherine May: People won't be able to hear this in the recording, but I just need you to know that it was the rubber end, but even so.

Kate Fox: Yeah, this is, you know, [00:51:00] I mean, this is, this is the thing. Neurodivergent resistance is not just resistance to To me, it's not a personal project only of, um, learning about your mask. It's a, it's a generally resistant project that says people and trees and interconnected systems are worth far more than being harnessed to the service of a, of a growth and productivity goal that we've never signed up for.

Kate Fox: And that has galvanized me. But at the same time, the irony of, imagine if it galvanized me that much. I was like, this is my mission. I'm going to die on that hill and use all my energy and spoons and oh, hang on. That's not going to

Katherine May: work, is it? I need to, yeah. That is the hard, that's the hard question.

Katherine May: Angela's asked, what do we both do to get some rest from overwhelm? Good question, Angela. Do we have an answer, Kate? I

Kate Fox: don't [00:52:00] know. I was doing really well, Angela. I was doing, I was Swimming would always help. Buddhist meditation, big on the Buddhist meditation, very good. Um, I would read when I needed to. I would watch telly when I needed to.

Kate Fox: Um, but in this time of increased overwhelm, none of those things particularly are working. So I mindlessly scroll on online dating sites at the moment. Who knows what will come from it that day? No, actually, it's interesting. So I'm, I'm, I'm thinking about, you know, how do you reimagine neurodivergent relationships and sexuality?

Kate Fox: So that is a kind of hyper focus. And it turned out that actually, Oh, I'm fulfilling the hyperfocus by doing one of the only things that's temporarily dopamine unsoothing. This is not, you know, this isn't, I'm not advocating this as a coping mechanism, [00:53:00] but it's currently, I need to get back to the swimming and the meditation and stuff, really, I really, really do.

Katherine May: Yeah, I'm the same, like, swimming, um, doing, like, going on a walk, like walking every day is such an important thing for me to do. And I, and it's of course the first thing to go when I get busy. Like that's, you know, I think making sure I have three square meals a day is massively important for me and, and breaking for lunch, you know, not, you know, Eating lunch on the fly, like taking a lunch break.

Katherine May: They're really simple, but I, one of the things I've noticed lately is that my son is so much better at regulating tiredness than I am, you know, and he, because he doesn't, and partly that's because of the way I've brought him up, and I, you know, I raise him in a way that I don't raise myself. Of course, but he, when he's feeling tired, when his brain is full, when he needs a rest, he takes a [00:54:00] rest and he sits down and he scrolls on his, uh, tablet and he watches TV and I will like flap around saying, Oh no, no, no, no.

Katherine May: I hope you know, Oh God, you know, you shouldn't be watching. And then it's like, No, he's doing exactly what he needs and I need to do that next to him, rather than telling him to stop it to look more productive. You're about to read a poem, I can tell.

Kate Fox: Oh no, I'm only, I'm getting, no, I'm getting it ready for the end bit.

Kate Fox: Oh. But yeah, going back to, that, so the scrolling thing, exactly. I have discovered, it's quite temporary, as of this week, the scrolling thing is the only thing that's working. Because my usual strategies and other people I can see are coming up, yeah, naps and things, of course, like normally, and three meals a day, so good on this.

Kate Fox: But there is so, yes, lads in their rooms on their video games and people saying, oh, that's all they do, they're just on their video. I can understand why that might be a concern, but actually, if someone is doing important self regulation and they're [00:55:00] recognising that's what they need.

Katherine May: A day at school is a lot, and actually, after that you need to watch geeky engineering videos for an hour.

Katherine May: It's not actually bad. Kate, would you like to close us off with a poem? Because this has been so lovely, and um, it's just so lovely to hear you read. I always love listening to you, so yeah. Let's, let's close with a lovely poem.

Kate Fox: Thank you, and a huge thank you for having me. Oh, absolute pleasure. Um, I did have a bit of a moment when I see where everyone is from, and there's people from all over the world.

Kate Fox: They're extremely cool. So I didn't, um, I didn't read this at my in person book launch last night because I worried that I could not pull off the intro. Earnestness that it required . And I thought that was a real pity because actually I, it's really heartfelt. It's a promise to the tree. It's a promise that I hope we will make.

Kate Fox: It's called trow, spelled T-R-E-O-W. 'cause it turns [00:56:00] out that's the old English word for tree, but it's also the word for true or vow. So tree comes from tr true or vow. So I reckon this is a promise we should make Dearest. Who we recognise as true, constellations radiating from the core of you, slowly cycling the seasons of your deep time, overseeing the speedy passing of our generations, with a constancy unhindered by concern for your own legacy.

Kate Fox: We are grateful for the protection of your shade, for the memories you have made, for the lives tiny and large you have nurtured, from the tips of your laden boughs to the depths of your mycorrhizal root, for the hope you have embodied again and again in your greening shoot. [00:57:00] We are so grateful. We are sorry for your shocks.

Kate Fox: May we find the will to properly care for all your kind as you in turn have cared for us. May you in future know only peace. May your open heart restore us.

Katherine May: That was so lovely. That made me feel incredibly peaceful. Thank you, Kate. That was lovely. And thank you so much to everyone who's been here. That has been fantastic.

Katherine May: I, I, what I really love is that, um, you know, we say something and everyone's like, Oh, here's the link for that. Like, that's just enormously wonderful and helpful. And it's like having a whole team of, um, Very British reference, Wombles looking after us. Americans were like, I don't know what that is. But then, you know, that's something for you to find out.

Katherine May: It's a very weird thing. Thank you everyone so much. Happy Poetry [00:58:00] Day. What a lovely way to celebrate. And please do check out all of Kate's wonderful places because if you're not following her already, you will love her. As I do. I'm going to say goodnight to everybody and, uh, yeah, thank you for, for being here.

Katherine May: Goodnight.

Bye.

Show Notes

It was National Poetry Day in the UK earlier this month and Katherine talked to Kate Fox about her new book, On Sycamore Gap, in an extra Book Club event. Kate’s book is about a very special tree in the north of England that was chopped down by vandals, but that has brought people together in the aftermath of its felling.

Katherine's book, Enchantment, is available now: US/CAN and UK

Links from the episode:

Join Katherine's Substack for a free reading guide, video recordings and transcripts

Find show notes and transcripts for every episode by visiting Katherine's website.

Follow Katherine on Instagram

Please consider supporting the podcast by subscribing to my Substack where you can join these conversations live!

To keep up to date with How We Live Now, follow Katherine on Instagram and Substack

———

Enchantment - Available Now

“Katherine May gave so many of us language and vision for the long communal ‘wintering’ of the last years. Welcome this beautiful meditation for the time we’ve now entered. I cannot imagine a more gracious companion. This book is a gift.”

New York Times bestselling author Krista Tippett